REUTERS | 11-22-2013

By: Richard Valdmanis on Reuters.com

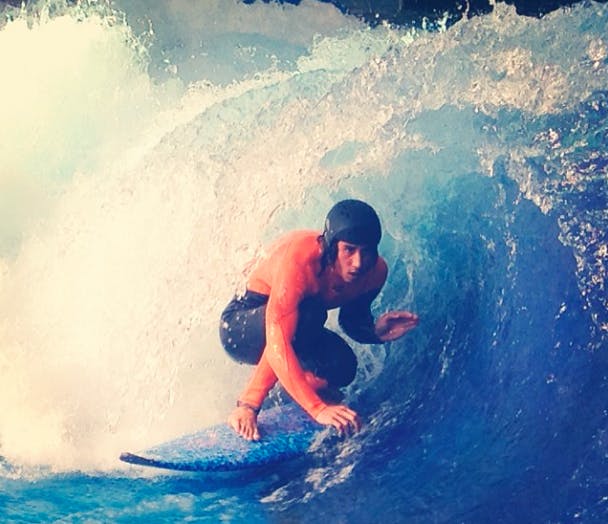

(Reuters) – A surfer drops down the face of a crashing swell, crouches low and stalls his board into the tube, achieving the sport’s ultimate goal of a ride inside the barrel.

But instead of being on a sunlit beach in Hawaii or southern California, this surfer is inside a glass-and-concrete building in New Hampshire – at America’s newest surf park, an hour’s drive from the Atlantic.

“Part of our mission is to bring surfing everywhere, including where there isn’t an ocean,” said Bruce McFarland, president of American Wave Machines.

The company’s SurfStream wave system is being used at the Surfs Up New Hampshire park in Nashua, which is set to open in December.

Surf parks have been around for decades, but a surge in the sport’s appeal and rapid advances in wave-making technology have triggered new construction in unlikely places such as South Dakota, Quebec, Sweden and Russia.

Using proprietary designs meant to emulate waves formed in nature, companies like American Wave Machines, Weber Wave Pools, Waveloch and others are racing to bring the ocean sport to the landlocked masses.

Fernando Aguerre, head of the International Surfing Association (ISA), said their efforts could be a big boost for surfing and businesses built around it.

“Surf parks will give the opportunity to learn to ride waves in a safe way to millions of people around the world,” he explained, adding it could also help ISA to make surfing part of the Olympic Games.

“Without man-made surfing waves, our Olympic surfing dream would be just that – a dream,” he said, adding that reliable, identical waves, virtually impossible to find in nature, are needed to insure fair judging in Olympic competition.

Surfing Inland

Once seen as a fringe sport, surfing now has around 35 million enthusiasts worldwide. It is a roughly $6 billion retail industry in the United States, according to the Surf Industry Manufacturers Association.

“The industry is doing a good job selling surfing as a lifestyle. It is fun. It influences culture, music, fashion, all that. It is imbedded. But it is hard for anybody who doesn’t live near the ocean to do,” said McFarland.

Surfers, desperate for a good wave, have sought out wind swells on the Great Lakes and tried surfing on river rapids and in the wake of passing barges on the Houston Ship Channel in Texas.

“There is definitely a huge demand,” said Matt Reilly of Surf Park Central, a website that tracks global surf park construction. “The speed of growth that you’re seeing is the result of improvements in technology and increases in efficiencies.”

The most commonly used surf park wave designs are modeled on standing river waves, where thousands of gallons of water are propelled against an immobile object to create a stationary curl.

At a recent Surfs Up New Hampshire test run, a handful of professional surfers – including Todd Holland, who was once ranked No. 8 in the world – carved up different types and sizes of standing waves in front of a panel of engineers and photographers.

“This is great,” said Holland. “Once you get going down the line, it feels just like racing a big section.”

Research has also been done on designs more closely related to waves at the world’s finest ocean spots, where a moving swell is produced that breaks when it hits shallow water along an artificial reef or sandbar.

Although less so than in the past, the cost of building an artificial wave system is still substantial. A standing wave system like the one in New Hampshire costs about $3 million to$6 million, while a traveling, or ocean wave, system is much more expensive.

Despite the surf park industry’s efforts to mimic real surf, McFarland, whose company is now also building a traveling wave park in Russia using his PerfectSwell technology, said artificial waves will always have their limits.

“We’re not trying to compete with the ocean, or replace it in any way,” he said. “But this is fun, and I think it is good for the sport and for people.”

(Writing by Richard Valdmanis; editing by Patricia Reaney and Gunna Dickson)